By Matt Rogerson

Check out Part 1, 2 & 3 of Matt’s Cronenberg pieces.

1. A BODY IN TRANSFORMATION: CRONENBERG’S BODY HORROR AS TRANSGENDER CINEMA

2. LET’S GET CLINICAL: CRONENBERG UNDER THE KNIFE

3. ADAPTATION: CRONENBERG GOES TO THE SOURCE

A Straight Story:

Cronenberg and the macabre melodrama.

Dead Ringers (1988)

M Butterfly (1993)

Spider (2002)

A History of Vioence (2005)

A Dangerous Method (2011)

Eastern Promises (2007)

Cosmopolis (2012)

Maps to the Stars (2014)

For critics, fans and documentarians alike, 2005’s A History of Violence is said to mark something of a waypoint in the career of Canadian auteur David Cronenberg

Considered his ‘comeback’ effort by many (despite arrivinging only three years after his previous film, Spider), the adaptation of John Wagner’s graphic novel is considered the beginning of an easily-defined third period in the director’s career: one of “intelligent, challenging and accessible movies for grown-ups” (O’Hehir, 2011). This noir thriller and essay on the innate violence of Darwinian evolution (Ebert, 2005) was filled with sex and violence (and combinations of the two) and yet it was, some remarked, quite restrained for a Cronenberg movie. Gone were the exploding heads, severed limbs, and bizarre fleshy protrusions, in favour of an exploration of more cerebral horrors.

As explored in the previous essays of this series, Cronenberg’s body of work has always been about the cerebral horrors, even though it has often used gory physical transgressions to manifest them. It was always our worries, about sex, identity and bodily transformations that were made flesh in the Canadian’s films. Despite this, there was (and remains) a distinct belief that 2005 marked a change in Cronenberg’s films.

A History of Violence was followed up with Eastern Promises, the director’s true departure from type. This story of Russian Mafiosi, FSB Agents and a midwife caught in the middle of gangland slayings, drugs and human trafficking in the backstreets and bathhouses of London marks the director’s first true departure from the horrors, thrillers and sci fi he had become known for since 1979 (the year Cronenberg co-wrote and directed Fast Company, a drag-racing exploitation drama film in the vein of John Frankenheimer’s 1966 Grand Prix, Will Zens’ 1967 Hell on Wheels, and Jack Hill’s 1969 Pit Stop).

Since then, Cronenberg has directed three further films: 2011’s A Dangerous Method; 2012’s Cosmopolis and 2014’s Maps to the Stars. Each of these films are probably best described as dramas (if somewhat peculiar ones), and have alienated many of Cronenberg’s older fans just as they have picked up new ones, garnered critical praise and seen the director win a clutch of awards.

This apparent change of direction in Cronenberg’s career is anything but. To fully understand the relationship of the Canadian’s latter-day fare to our beloved umbrella of ‘genre cinema’ that traditionally contains horror, thriller and sci-fi, one must look back – not only to the director’s previous works, but to the 1940s, and a slew of supposed ‘horror’ films helmed by various directors under the auspices of writer/producer Val Lewton.

In the early 1940s, Hollywood Studio RKO’s reputation (and bank balance) was suffering, following a pair of expensive flops by Orson Welles (namely Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, both yet-to-become-classics that had drained the picture house of both their profits and their patience in Welles). Recognising the potential for turning a profit from very little outlay, the studio moved into the horror market with the intention creating a viable alternative to the Universal Monster movement (which was still successful at this stage, but starting to run out of steam due to its increasingly diluted output) and turning its fortunes around.

Val Lewton was hired by RKO purportedly by mistake – the story goes that the picture house mistook him for a horror novelist (a description of Lewton that he wrote horror novels had alluded to their quality, rather than genre). Lewton had actually got his start writing novelizations of popular movies, before becoming an assistant to David O Selznick and working (often uncredited) on movies such as A Tale of Two Cities and Gone with the Wind. Lewton was named head of horror at RKO, offered $250 per week and told to work within three guidelines:

1. Each film would be made for less than $150,000

2. Each film would be less than 75 minutes in length

3. The Studio would supply the film titles

Beyond these, Lewton had full creative control over his output, something which he relished. Intent on making movies that interested him, Lewton dispensed with the traditional chills and devised a series of dark, twisted psychological melodramas. He would joke of his own formula for horror:

“A love story, three scenes of suggested horror and one of actual violence. Fade out. It’s all over in less than 70 minutes” (Wierzbicki, 2012)

If this was his method in essence, his output became so much more – dark, dreamlike productions, laced with melancholy and morbidity, and an obsession with death’s icy grip on life. Lewton would work with a group of loyal in-house directors (Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise and Mark Robson) whom he would mould in his chosen style, still working within the confines of the horror genre but showing just how much could be achieved within those confines by a ‘serious’ filmmaker.

The films that came out of RKO during Lewton’s tenure were complex, morbid and melodramatic, centring on very personal horrors and crises; on the psychological and the existential, and very often on themes of identity.

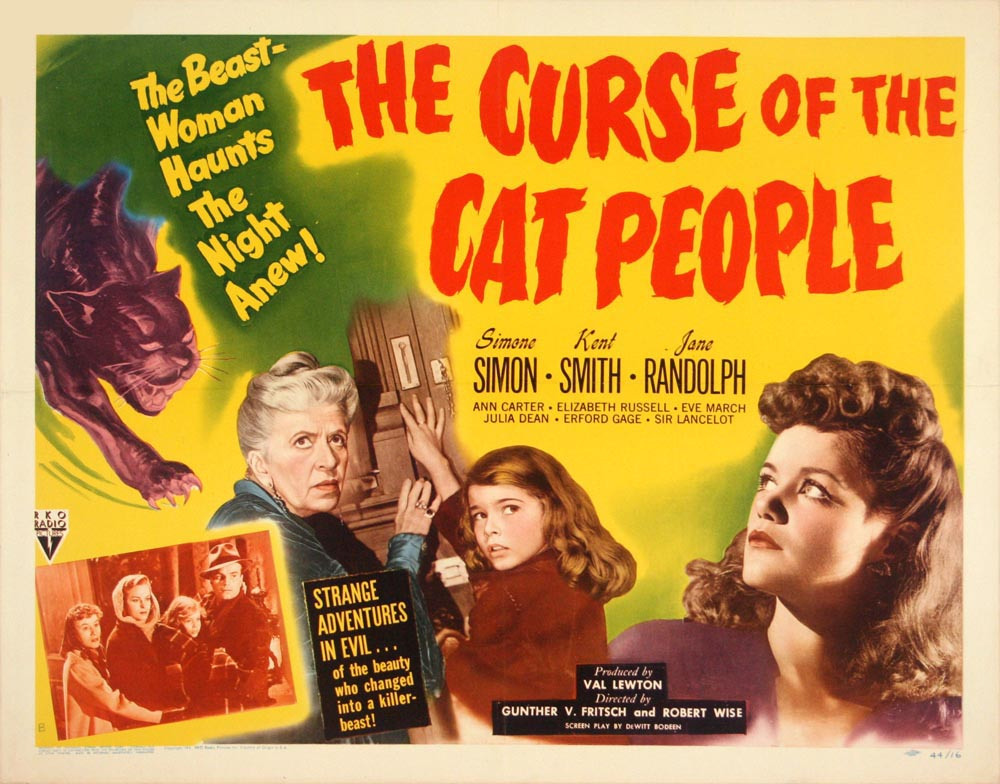

Jacques Tourneur’s seminal Cat People (1942) proved a study in irreconcilable sexual otherness (a common Cronenberg trope) and evoked the difficulties faced by foreign-born immigrants. Though it has moments of horror, including the ambiguous hints that Simone Simon’s Serbian fashion illustrator Irena may or may not transform into a wild panther, and a swimming pool scene said to have inspired Dario Argento’s Suspiria, Cat People remains very much a drama about human beings and the crises that lurk within them. Its sequel, Curse of the Cat People (1944) was even further removed from the comfortable confines of the traditional horror movie. This dark tale about a solitary child and her imaginary friend (the ghost of Cat People’s Irena, once more played by Simone Simon) would use the character of a vulnerable child to challenge the dark vagaries of the adult world. Six year old Amy’s (Ann Carter) private vision shows a delicate reaction to loss, where her father’s traumatized reaction to the same loss (his dead wife) is much more damaging and self-destructive.

Mademoiselle Fifi (1944)’s period drama set in Prussian-occupied France, explored class barriers, paranoia in distrust between the French and the Prussians, and an exploration of class and gender roles (Simone Simon’s Elizabeth, and her successful gamesmanship undermines the arrogant, superior men and strikes the first blow for French freedom). The Ghost Ship (1943) featured a seafaring vessel all too free of the supernatural, focusing on the conflict between the titular ship’s Captain and Officer, while the many interesting players in the ship’s crew meet a number of horrible deaths. Horror mainly in its atmosphere, its sense of dread and the inevitable, The Ghost Ship is (for all its lack of ghosts) a truly haunting picture, and one all too realistic monster in the Captain – a man who wields complete control over his crew like an angry God and a manipulative child rolled into one, his competing identities coexisting to instil utter fear in his sea-bound subordinates.

While discussion of 1940s RKO black and white curios may seem a million miles from the works of a Canadian body horror auteur, they are far closer to Cronenberg’s work than many realise.

Consider Dead Ringers, Cronenberg’s 1988 adaptation of the dramatized life story of twin doctors Stewart and Cyril Marcus (reimagined as Beverly and Elliot Mantle, realized by Jeremy Irons in a stunning dual role). Released at the height of the director’s body horror output (following on from 1983’s Videodrome and 1986’s The Fly), Cronenberg’s adaptation eschews the gory special effects of his earlier works in favour of an exploration of twin damaged psyches, of “questions of identity, the mystique of surgery, and male inability to come to terms with the mysterious folds of women's minds and bodies” (Newman, 2000). It is the relationship between the brothers, and more importantly their relationship with Geneviève Bujold’s Claire, that dominates the film and provides its moments of horror. The brothers undergo a descent into a very personal hell, and Cronenberg’s treatise on the human condition and self-realisation, all the while maintaining an ambiguity that ensures audiences are never certain precisely which of the twins they are observing. Cronenberg expertly denies the audience the certainty of whether Beverley or Elliot are onscreen. Kat (2015) notes the idea of male hysteria in the film, with the two male twins presenting what is more usually considered a ‘female’ behaviour, a heightened emotional state resulting in outbursts and histrionics. While this ties back into the themes of gender identity (Tan, 2018), it also sits very much at home in the familiar trappings of melodrama, a very deliberate technique employed by the director.

In the midst of his period of adaptations, David Cronenberg directed David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, a staged tale of a French diplomat Gallimard (Jeremy Irons) and his infatuation with a transgender opera performer and spy Song Lilling (John Lone).

Hwang’s play, a reimagining of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s Miss Saigon, is a complex and problematic drama that undoes some of the wrongs of its predecessors but adds new ones of its own (and Cronenberg’s film adaptation, sadly, builds on them). Hwang’s play (and self-penned screenplay that Cronenberg worked from) undoes the yellowface, tokenism and harmful white-saviour-meets-submissive-Asian-woman tropes of its predecessors by switching roles. Here, Gallimard and Liling begin an extramarital (and illegal) love affair that, refreshingly, does not provide the main conflict of the narrative. Gallimard and Liling are, to an extent, free to love who they want to love. Hwang’s play does not judge them for their desire to be with each other. Instead, Liling’s identity is. Liling is a Dan performer, a female Peking Opera role actually played by men. Throughout, there is confusion as to Liling’s actual sex, but Liling has a second identity – they are a spy for the Chinese government, and Gallimard is their mark.

Where Hwang’s play (and Cronenberg’s film) removes one element of problematic casting, it unfortunately introduces another: Liling is played, on the stage (by Jin Ha) and in the film (by Lone) by cisgender men. While the play garnered much praise for righting the wrongs of its predecessors, it is now somewhat of a disappointment that it has not progressed or adapted to explore non-binary or transgender identities (Lewis, 2017); nor does it provide an opportunity for a non-binary or trans performer to bring it to life.

This provides a further disappointment in Cronenberg’s adaptation: the auteur of bodily transformation, whose entire oeuvre deals with questions of identity, had perhaps the perfect opportunity to further explore his gender positive themes in his 1993 film, but instead opted to (for the lack of a better turn of phrase) play it relatively straight. Time Out (1993) lambasts the director’s lack of radicalism, his refrain from truly dissecting “the extremities of desire and the slippage of sex roles” and instead relying on a conventional narrative about a spy and their mark, while Maslin (1993) considers Gallimard’s pursuit of Liling to be “nocturnal and strange”, further adding to the othering of both Liling, and Liling and Gallimard’s relationship.

What we do get from Cronenberg is a remarkable melodrama. The relationship between the two leads offers the same subversion of stereotypes as Hwang’s play, and Gallimard’s capacity for self-delusion is ably presented on the screen by Neeson, his turn as the arrogant masculine imperialist who is in fact incredibly naïve to Liling’s political manoeuvres and gamesmanship, and there is an ambiguity to the film’s themes that lends it a peculiar air. The blossoming romance between the leads turns to bitterness as Liling’s betrayal is revealed, and Gallimard rejects Liling in a last ditch attempt to retain some form of dominance. This, of course, only serves to make Gallimard even more pathetic.

That Spider (2002), the adaptation of Patrick McGrath's tale of trauma and psychosis, followed Existenz (a very familiar, comfortable Cronenberg film, nestled somewhere between Videodrome and Scanners in terms of content and themes), might explain why it seemed to fly under the radar, and not really catch on with the director’s usual fanbase. This (along with M Butterfly and Dead Ringers before it) is the film that really marks the change in the director’s intent. Ever since his adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dead Zone (which marked, according to Ebert, Cronenberg’s transformation from a director of schlock horror to one capable of crafting “three-dimensional, fascinating characters” (Ebert, 1983), the Canadian has brought his complex characterizations more to the fore – through Johnny Smith, Beverly and Elliot Mantle, through Rene Gallimard and Song Lilling, a through line to the portrayal of Dennis Cleg.

Using expressionistic tropes, Spider spins the web Cleg (Liam Neeson) in the form of a melodrama, played via the fractured, tangled mind and memories of its unreliable narrator. We see what Spider sees, how Spider sees it, and are charged with working out what is true and what is fabricated. In essence, the film is a melodrama. It deals with a child growing up in a working class London suburb, and the effect his parents’ dysfunctional relationship has on his formative years. The tale of Spider’s amoral father (Gabriel Byrne) and prostitute mother (Miranda Richardson) is not far removed from a soap opera. There are dramatic highs and lows, twists and turns and convolutions, each plot point weaved like the strands of a spider’s web, and the thread webs of Cleg’s obsessive compulsive behaviour as an adult. Even the murder that the film’s mystery hinges upon carries a very kitchen sink trope – Spider murders his mother not with an axe, meat cleaver or machete, but by gassing her in the kitchen. The horror in the film comes not from the recognised Cronenbergian body horror tropes, there are no exploding heads or human fly monsters, just the twisted, damaged psyche of a man attempting to recover from a boyhood trauma (albeit an extreme one).

Throughout Cronenberg’s career, the director has rooted his horror in melodrama, very often employing tropes that date back to the films of Val Lewton and RKO Studios: The histrionics of the Mantle brothers of Dead Ringers sit in parallel to the angry God/manipulative child antagonist of The Ghost Ship; Simone Simon’s Irena in Cat People could be the uptight mother of Rabid’s Marilyn Chambers or Crash’s Holly Hunter and Deborah Unger, repressing her sexuality for fear of it unleashing a beast, while her filmic children unleash theirs and cause utter havoc. M Butterfly traces a line back to Lewton and Robert Wise’s Mademoiselle Fifi. In the expressionism of Spider, Cronenberg recalls Jacques Tourneur’s methods of linking characters inextricably with their surroundings. It is these tropes and features, found throughout Cronenberg’s entire career, that inform his latest incarnation. While the likes of A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis and Maps to the Stars may have alienated hardcore horror fans, their director hasn’t strayed too far from his genre beginnings, as he seeks to explore existential horrors in his third cycle as filmmaker.

And that’s it! I’ve spent the last four weeks exploring David Cronenberg for a couple of reasons:

To reconnect with a director who has always intrigued me, but has alienated me at times. I have always admired the work of the Canadian but sometimes struggle to engage with it. In preparing this series, I have tried to explore some of the less-documented aspects of the director’s filmography, and I hope I’ve been successful in doing so.

As a “thank you” to Alex, head honcho of Beyond The Void Horror Podcast and LongLiveTheVoid.com. Alex spins a ridiculous number of plates to keep the weekly podcast entertaining and provide the website with regular fresh content, and is one of the main reasons I kept writing when, a few years ago, I was frankly ready to quit for good. David Cronenberg is Alex’s favourite director, and I wanted to write a series that would not only entertain you, the reader, but also be of personal interest and enjoyment to Alex. Thanks buddy.

So what next? Well, I haven’t a clue. If you’ve enjoyed reading my Cronenberg series, my Giallo series, or any of the other reviews, interviews and essays I have posted here, please do get in touch and let me know what you’d like me to tackle next! Either leave a comment below, or hit me up on twitter @bavalamp, and inspire me on my next Odyssey into the margins of horror cinema.

Matt Rogerson, July 2019.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING:

Ebert, R (1983) The Dead Zone [online] Available at: https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-dead-zone-1983 [Accessed 23 June 2019]

Ebert, R (2005) A History of Violence [online] Available at: https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/a-history-of-violence-2005 [Accessed 2 July 2019]

Graveley et al (2014) The Glitter of Putrescence – Val Lewton at RKO [online] Available at: http://hcl.harvard.edu/hfa/films/2014janmar/lewton.html [Accessed 2 July 2019]

Holden, S (2003) FILM REVIEW; Into Sinister Webs Of a Jumbled Mind [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/28/movies/film-review-into-sinister-webs-of-a-jumbled-mind.html [Accessed 20 June 2019]

Kat (2018) Melodrama Research Group: Summary of Discussion on Dead Ringers [online] Available at: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/03/26/summary-of-discussion-on-dead-ringers/ [Accessed 2 July 2019]

Lewis, C (2017) “M. Butterfly” Surprisingly Relevant [online] Available at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/m-butterfly-surprisingly-relevant_b_59f28708e4b05f0ade1b5625?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAM_anBoWdz0ELuIefhQffI3IZEBinA5yIBi0Y3hQv58asKPKidUXi59kY-AziQhP24mDmLR4sKOs6thojVthHQjyTeZqLwjoF79nPJLaqk9mREnYxy0mZbvDMq8HiUbbz9dGDlNlSIOzP1Dg13PsW68w6q65Qp_6H5FWnu5Q82Ut [Accessed 2 July 2019]

Maslin, J (1993) Seduction and the Impossible Dream [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/01/movies/seduction-and-the-impossible-dream.html [Accessed 23 June 2019]

Newman, K (2000) Dead Ringers Review [online] Available at: https://www.empireonline.com/movies/reviews/dead-ringers-review/ [Accessed 2 July 2019]

O’Hehir, A (2011) David Cronenberg: It's as if my old movies don't exist [online] Available at: https://www.salon.com/2011/12/03/david_cronenberg_its_as_if_my_old_movies_dont_exist/ [Accessed 2 July 2019]

Tan, L (2018) What Transpires Within: Self-realisation and Trans Narratives in ‘Dead Ringers’ [online] Available at: https://muchadoaboutcinema.com/2018/07/28/what-transpires-within-self-realisation-and-trans-narratives-in-dead-ringers/ [Accessed 10 March 2019]

Wierzbicki, J (2012) Music, Sound and Filmmakers: Sonic Style in Cinema. Abingdon-on-Thames; Routledge

The son of a VHS pirate, Matt Rogerson became a horror fan at a tender young age. A student of the genre, he is currently writing his first book (about Italian horror and the Vatican) and he believes horror cinema is in the middle of a new golden age.

Have you listened to our HORROR Podcast? This week on Beyond The Void Horror Podcast . This week we decided to dive into a few Robot movies that “wear peoples faces as masks”. We watched Chopping Mall (1986) & The Vindicator (1986). Two so bad it’s good robot mayhem movies with loads of trivia and more. Check it out! Listen/Subscribe on iTunes here!