by Mark Doubt

ALL THE COLOURS OF CREATION: PART 1

Giallo.

Meaning ‘yellow’ in its literal sense, the term was adapted from the pulpy whodunit thriller novels published in Italy since the 1920s. What began as the circulation of the works of Edgar Wallace and Agatha Christie would soon be exploited by Italian authors writing under anglicised pseudonyms and ensuring the books contained typically lurid content – often very violent and sometimes quite sexually titillating and misogynistic.

The film movement that followed, however, would come to mean something much more.

As a cinematic phenomenon, Giallo also took its cues from the crime films of Danish and West German cinema (the latter known as krimi). These movies (such as The Secret of the Black Widow and The Phantom of Soho, both directed by F.J. Gottlieb) were in turn frequently based upon or took inspiration from the crime/mystery novels of Edgar Wallace, and themselves formed a bizarre genre – one that straddled crime, noir, expressionism and horror.

The Giallo movement rose to prominence in the early 1970s, as a host of genre directors who would later achieve infamy across the world used the template to help bring this dark, stylish cousin of horror to the western world. The likes of Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci and Sergio Martino would become synonymous with Giallo…but more on them later.

This story begins in 1963, with a cinematographer turned director whose work would play a large part in the creation of not one, but two new genres.

Born in the summer of 1914, the son of Italian special photography effects supremo Eugene Bava would become not only one of the country’s best known directors, but an auteur of international repute based largely on his work in the horror and giallo genres (despite making movies across virtually every genre cinema had to offer).

Mario Bava spent 20 years learning the ropes as a cinematographer before making his directorial debut. This lengthy pre-career mastering the technical aspects of helming a movie would make Bava a master of soliciting psychological reactions from his audiences via technical skill and trickery, and see him compared not only to Alfred Hitchcock but to the likes of Godard, Fellini and legendary French cinematographer Henri Alekan. Bava would go on to have several notable successes and create a very varied portfolio in the 1960s, turning his hand to most genres and flourishing in each. It was, however, the Hitchcock influence that would see Bava redefine the psychosexual thriller and put Italian genre cinema on the map.

The early 1960s would see Bava create a string of films that have earned their place in the annals of horror history, such as the Barbara Steele-starring gothic chiller Black Sunday (1960) and a portmanteau masterpiece that inspired British heavy metal musician Geezer Butler to name his and Ozzy Osborne’s new band - Black Sabbath (1963).

Away from these horror hits, a pair of dark thrillers would birth the genre we now know of as Giallo.

THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1963)

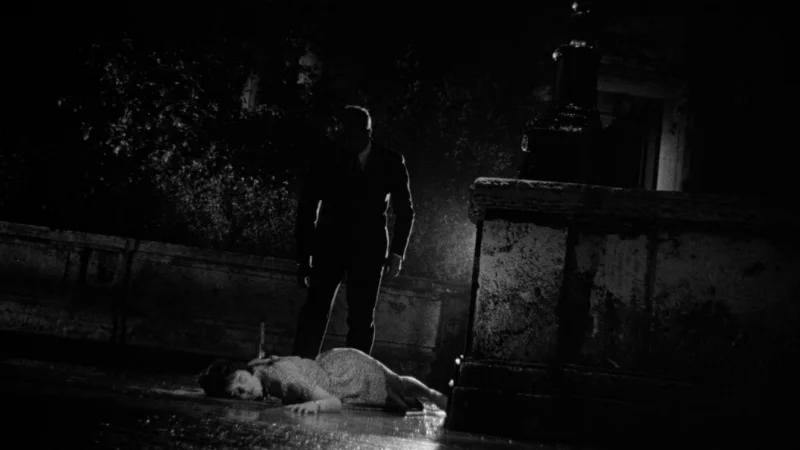

Bava’s 1963 black and white thriller is often identified as the starting point for Giallo, the protoplasmic pool from which the genre was first formed. In fact, it takes its inspiration chiefly from the noir films of Alfred Hitchcock and Robert Siodmak (with a good dollop of Fritz Lang’s expressionism thrown in for good measure) and the crime novels of Agatha Christie. The story of a bored American girl (Letícia Román) who witnesses a brutal murder in a foreign land and (when the local police and doctors refuse to believe her) begins a search for the killer, it is closer to a whodunit than a horror film. Though dark, moody and violent, it has its lighter, almost tongue in cheek moments, as it presents us with a puzzle to solve alongside the lead character then allows us to follow her through a veritable maze of twists and turns.

It has many of the visual and narrative elements we come to associate with Giallo – a black-gloved killer, a mystery, incompetent police and an outsider turned sleuth – but in many other respects it is quite far from the genre. Giallo would become defined by its ostentatious production design and lurid colour palette, fetishized violence and sexuality. If anything, this film should be considered Bava’s proto-gialli. The visionary director would not cement the elements of the genre for another year…

BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964)

Bava’s 1964 clash of murder and glamour in an Haute Couture fashion house depicts a series of models dying in increasingly inventive ways at the hands of a mysterious, masked killer. This stylised, psychosexual murder mystery has seen Bava compared to Federico Fellini, his concentration on the female form – established as the essence of sexuality, then punished with violence – married with beautiful imagery, technical mastery and realistic violence would not only echo cinema’s greats but would influence the likes of John Carpenter, Wes Craven and Sean Cunningham.

While The Girl Who Knew Too Much is largely credited with birthing the Giallo genre, Blood and Black Lace was the first of the auteur’s movies to marry all the elements of the yet-to-be-named movement in one movie. The film marries the established tropes of “The Girl…” with the superb gothic atmosphere of Black Sunday and the exaggerated, lurid colour palette (already adopted by US B-movie stalwarts such as Roger Corman and Herschell Gordon Lewis) that the later genre movies of Dario Argento and Sergio Martino would become known for. Blood and Black Lace codified the elements that make up the genre – the murders (often elaborate); beautiful women (as victims); lurid colour; a sense of irony. There is also a sense of the abstract – by day, the world is a rational, logical place; by night, things change – symbolised by opulent colour, by shadows that transform the physical places that seemed so innocuous into foreboding labyrinths.

The keen eyed will also spot the beginnings of another sub-genre yet to be born – but more on that another day.

Once Bava had provided the inspiration, other directors in his native Italy were not far behind. Screenwriter Mino Guerrini (who collaborated on the screenplay for The Girl Who Knew Too Much) would soon become a prolific director himself. Films such as The Third Eye (1966) and Murder by Appointment (1966) would see elements of Bava’s gothic horror, flamboyant style and dark mystery infused with a healthy dose of comedic timing. While Guerrini’s films would not quite solidify the genre, they bore many elements of the perfect Giallo recipe. Angelo Dorigo’s trade in Agatha Christie-style mysteries saw him direct A for Assassin (1966) about a warring family gathered together for the reading of a will who are slowly whittled down by an unknown assailant’s dagger. One year later he would return with Killer Without A Face (1967) a noir thriller replete with a former detective turned bodyguard, femme fatale and various seedy locations (such as a meat packing plant).

Before long, Italy had a burgeoning new genre on its hands. The Monster of Venice (1965, dir Dino Tavella) featured a serial killer in scuba gear; Libido (1965, dir Ernesto Gastaldi) features a diabolical plot in the villa of a sex maniac; The Sweet Body of Deborah (1968, dir Romolo Guerrieri) is a tale of murder, suicide, a voyeur and death threats. More and more lurid thrillers were released year on year, often with titillating titles and exploitative content.

The Giallo was born.

It was not until the 1970s that the genre began to truly take off outside of Italy. Ornately-titled productions such as Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) and The Cat O Nine Tails (1971), Lucio Fulci’s Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971) and Sergio Martino’s The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh (1971) would further explore the themes, tropes and devices that Bava had established, elevating the exploitative base content into artful, stylish cinema.

ON FRIDAY: We take a look at how Bava returned to Giallo tropes in 1971 and helped set the blueprint for the modern slasher genre.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

Adams, Simon (2017) Viva Bava, Celebrating a Master Craftsman

https://www.rogerebert.com/balder-and-dash/viva-bava-celebrating-a-master-craftsman

Anderson, Kyle (2014) Maestro of the Macabre

http://nerdist.com/maestro-of-the-macabre-the-top-5-mario-bava-movies/

Conterio, Martyn (2016) Where to begin with Mario Bava

http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/where-begin-mario-bava

Gonzales, Ed (2003) Kill, Baby…Kill!

http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/kill-baby-kill

Hughes, Howard (2015) The Glamour House of Horror

(Available on the Arrow Video Blu Ray release of Blood & Black Lace)

Ishii-Gonzales, Sam (2004) senses of cinema – Mario Bava

http://sensesofcinema.com/2004/great-directors/bava/

Jones, Alan (2002) Joe Dante Remembers the Genius of Mario Bava

Shivers #83: November

Kenny, Glenn (2015) The Politics of Murdered (and murderous) Women, Part 1: Mario Bava’s “Blood and Black Lace”

Mason, Scot (2014) 10 Essential Mario Bava Films Every Horror Fan Should See

http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2014/10-essential-mario-bava-films-every-horror-fan-should-see/1/

Needham, Gary (2002) Playing with genre – An introduction to the Italian giallo

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/11/needham11.php

Psycho Analysis: Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava and the Giallo (2015). [Blu-ray]. UK: Arrow Video

Mark loves horror, it's history, Art House films and he loves to make art.

Be Sure to Check out his work

Have you listened to the latest Beyond The Void Horror Podcast? This week we talk about two movies about demons. The Church & The Keep. It's a fun episode. Listen here or subscribe/listen on iTunes HERE!