By Mark Doubt

Monsters of the Wild Frontier

1970s Horror and how the West was Whitewashed

by Mark Doubt

As news breaks of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s potential return to television and movie screens in new chapters of the franchise, Mark Doubt gives us his retrospective of the cultural subtext of the original alongside three other seminal 1970s genre movies.

In the mid-1970s, a new type of director (and movie) would emerge from within the horror genre. Jettisoning the gothic, the literary, and the supernatural in favour of the visceral, the brutal and the graphic violence of remote, inhospitable environments and untamed, unfamiliar monsters that were once people, not only in the USA but Australia as well. As part of the New Horror and the Australian New Wave movements respectively, directors Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper, Peter Weir and Colin Eggleston would plot new courses for the genre, away from the supernatural chills and thrills of the previous decade. Instead, they would rise to infamy telling tales of suburban families pitched in mortal combat with subhuman savages and with nature itself, in exercises of gruelling terror, survival and revenge. Those films were:

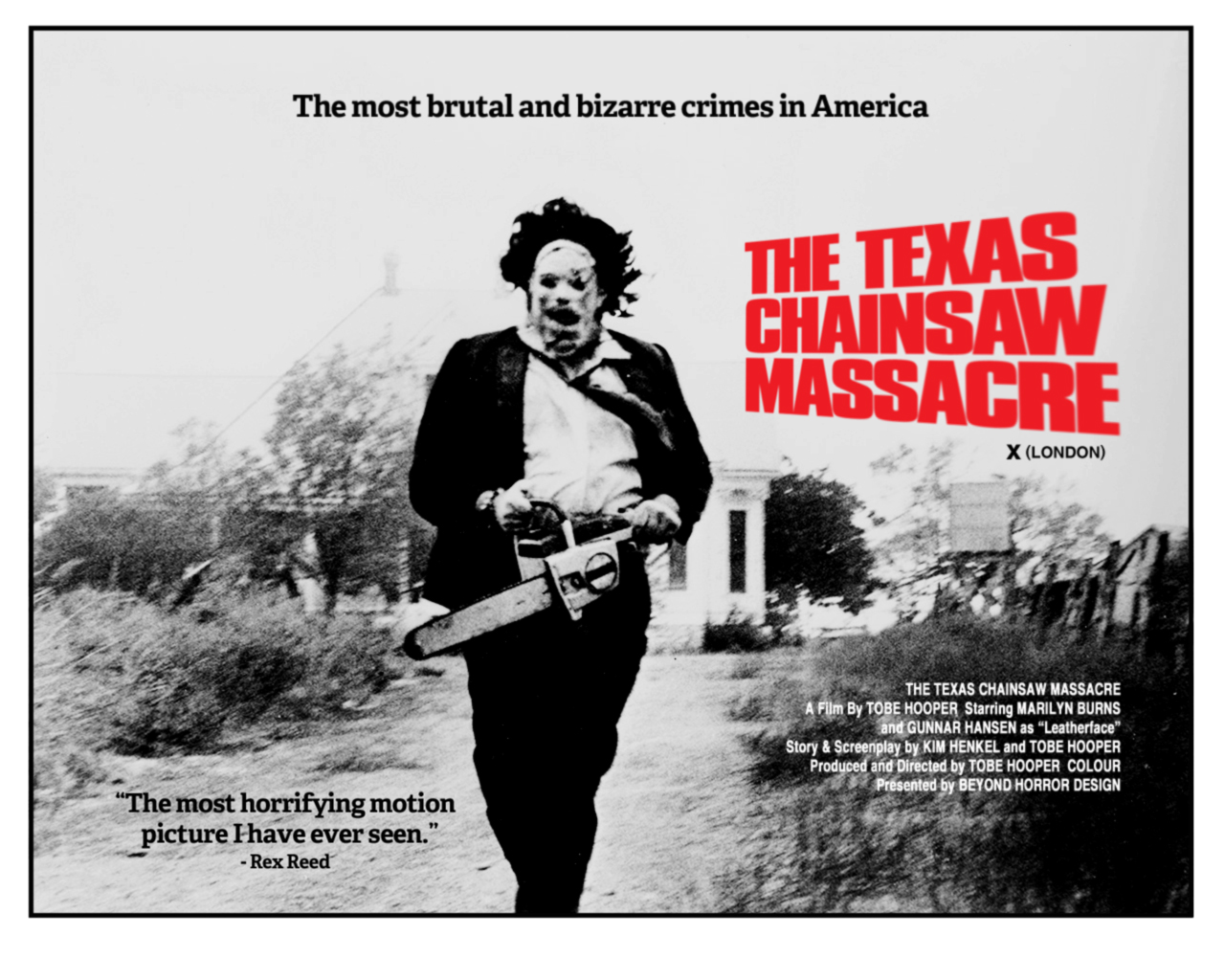

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974, dir Tobe Hooper)

One of the most influential and emulated movies of the last 40+ years, Tobe Hooper’s tale of hapless hippies captured, trapped and tortured by the secluded Sawyer family that wear human skin and wield chainsaws and meat-hooks (said to be inspired by real life killer Ed Gein) captures and presents the most visceral fears of all mankind, and forces audiences to experience a genuine terror they will not soon forget.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975, dir Peter Weir)

Adapted from Joan Lindsay’s novel, a movie of supernatural mystery and sexual hysteria deals with the disappearance of three schoolgirls and their teacher, who vanish on a trip to a local geological outcropping (the titular Hanging Rock), never to be seen again.

The Hills Have Eyes (1977, dir Wes Craven)

This tale of survival and revenge was based loosely on a true story – the mountain-dwelling cannibal family that wreak havoc on the mild-mannered city folk are said to be inspired by Sawney Bean and his family, a wild Scottish clan who murdered and ate whomever strayed into their territory during the Middle Ages. In the movie, the story is transposed to a nuclear testing range in the Nevada desert, with the mutant clan of murderers and rapists setting upon (and eventually defeated by) the all-American Carter family.

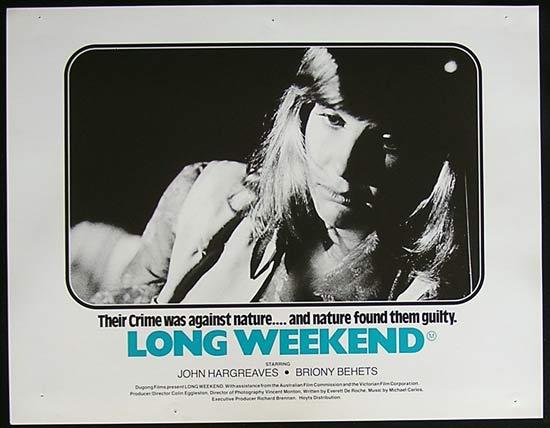

Long Weekend (1978, dir Colin Eggleston)

A young couple on vacation in the Australian wilderness fall foul of each other and of nature itself. As tensions escalate between them, the environment they show disdain for turns against them and wreaks its revenge.

To fully understand these films that shook cinema to its core in both the US and Australia, it is important to understand a particular subtext which informs them: that each of the filmmakers’ efforts are actually born of another time, and another genre altogether. These four iconic films are steeped in the tropes and lexicon of the Western, of new frontiers and man’s attempts to tame them, and they bear the subtext of two nations’ pioneer past and the effect of European settlers on ancient lands and indigenous peoples.

Yes, Wes Craven’s survival/revenge thriller, Tobe Hooper’s exercise in despair and Peter Weir and Colin Eggleston’s tales of environmental terror are as much about the romanticism (and fetishizing) of the New Frontier and the adventures (fictional and otherwise) of Ethan Edwards, Cavalry Captain Case McCloud and Bush Ranger John Vane as they are about murder, revenge and exploitation. Each of these four studies in terror borrow from genuine American (and Australian) indigenous history and transplant it into recognisable modern day scenarios.

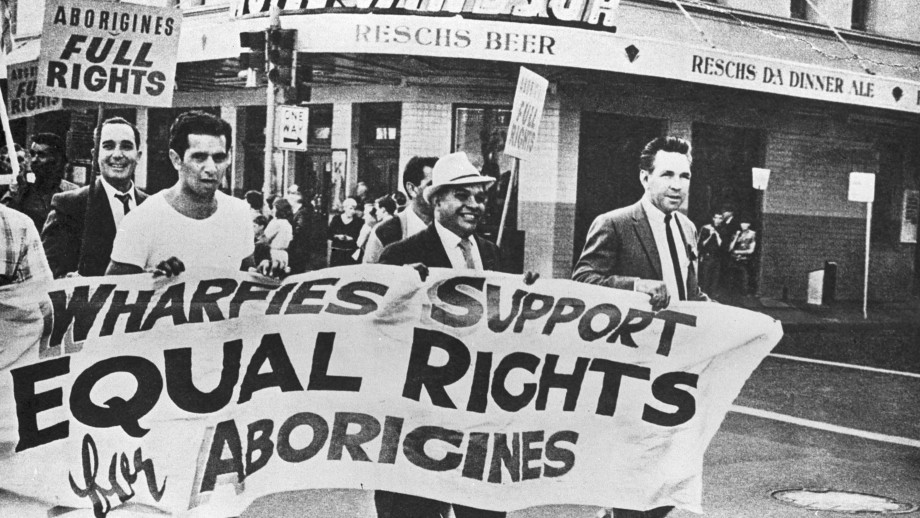

In the 1970s, the people of both countries were undergoing a period of intense introspection. In the US, the events of the Vietnam War had left Americans wondering about their place in the wider world, and their treatment of their own people. In Australia, the Aborigine Referendum of 1967 had prompted the country’s immigrant population to give greater consideration to the indigenous peoples their new societies had usurped.

In the case of both The Hills Have Eyes and Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the remote Badlands of Nevada and Texas represent the new wild frontier, a savage land both alien and genuinely very dangerous for society’s modern pioneers – the suburban family. Wagon trains become station wagons and camper vans; the wholesome all-American family and the Australian ‘Bruce and Sheila’ suburbanites are the new settlers, venturing from the safety of the civilised city to sample the expansive wilderness (by way of the fabled Great Road Trip), only to find the native savages waiting, watching, ready to pounce and show the pioneers that they have entered no-man’s land. In these fictional accounts, the Native American and Aboriginal Australian tribes are replaced by bands of mutants, cannibals and assorted monsters indigenous to these remote, inhospitable Badlands, but the parallels are indiscreet.

AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL

"A typical American family - they didn't want to kill, but they didn't want to die."

In this pair of modern US classics, the central characters are trialled and tested in horrific ways. Attacked, raped, and murdered, those that survive are forced to find their mettle: to circle their wagons, reach deep within themselves, and fight back if they are to tame the savage lands they have entered. In Craven’s film, Jupiter’s wild clan steal the Carter family’s infant child, echoing both the various accusations levelled at Native American savages over the years and the plot of John Ford’s divisive Western, The Searchers (itself lauded a cinematic masterpiece by some, damned for its portrayal of Native Peoples by others). As the film continues, the message is that our civilized heroes have more to lose, and are therefore capable of not only survival but (in the case of Hills) more extreme violence than the savages who have nothing.

In Texas Chainsaw, the very name and appearance of the most iconic antagonist – Leatherface – recalls not only the (oddly revered) serial murderers Ed Gein, Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer. The customs of Native American and Inuit tribes, who would not only wear animal hides but create masks and dolls made of the same, are overtly apparent in the film’s chief antagonist and his costume.

In many ways, the message delivered by Hollywood had not changed since the films of the John Ford era. The ‘heroes’ are in truth no more than trespassers – at best naïve, at worst invaders, venturing into territory that is not theirs to take – and yet they are portrayed as innocents, loving families on a voyage of discovery who have done nothing to deserve the evil visited upon them by the natives. In each movie, the narrative is the same – first attacked and decimated by the natives of these barren lands (establishing the pre-supposed guilt and monstrosity of native peoples, who in truth did no more than try to protect their homes and their cultures against invaders), our heroes rise up, overcome, and wipe out their attackers, bravely conquering the land for suburbanite kind – that nobody literally stands atop a hill and sticks a flag in the ground at the end is, frankly, a surprise.

To view both The Hills Have Eyes and Texas Chainsaw Massacre in this context adds an extra, all too socially-relevant layer of horror to proceedings. Not only are they violent, graphic, shocking and explicit, but they also (by manner of the subtext) further promote the whitewashing of US history in the caricaturing of native peoples into wild, inhuman beasts. The idea that history is written by the winners is truly evident here, in this pair of films that take the redrafted annals of the American frontiers (with the white settlers long since accepted as brave, pioneering heroes) and update their stories to present day.

It is important to acknowledge that this was not necessarily the filmmakers conscious intent (though, even unconsciously, it can be viewed as problematic).The beauty and curse of subtextual analysis is that films can be read in a number of ways – including ways the directors may never have intended. Both Hills and Texas Chainsaw can be correctly read as multi-layered commentaries on Vietnam/Watergate-era cynicism and the schism that existed between different elements of US culture.

Influence, however, is a many-tentacled beast, and young filmmakers of the 1970s would have grown up in the 1950s, when the Western genre was at peak popularity, and the US was establishing legislation which meant the country’s Native People would relinquish their sovereignty and be forced to leave their reservations to be ‘relocated’ to White America’s urban settings, suffering poverty, ill health, emotional anguish and a loss of cultural identity in the process (Picture This, no date). The US Federal Government’s Public Law 959: the ‘Indian Relocation Act’, was essentially genocide by homogenization, and both Hooper and Craven were raised in the time that its effects were beginning to take root in the American consciousness, leading to protests, civil disobedience and acts of peaceful occupation such as the Native American occupation of Alcatraz in 1969.

In addition, personal experiences on the road came into play, at least in Craven’s case. On a motorcycle road trip, the erudite and conservative Craven had stopped in the Nevada desert to eat and refuel. Here, Craven had come under attack, as a trio of young local men in a pick-up truck fired arrows that narrowly missed the young man before threatening to murder him. According to Zinoman (2011), this altercation provided a seed of inspiration for what would become The Hills Have Eyes. The young men that attacked Craven were white Americans – a little on the wild side but otherwise like him – but the experience of arrows whistling past one’s head does conjure a much different image in the barren deserts of America.

Filmmakers do have a responsibility to use their art in the pursuit of truth, and America’s “truth” was sadly fictionalised. History is written by the winners, and the winners had been the white settlers, creating and perpetuating the myth of Native savages in order to have the history books see them as the heroes.

The average viewer, therefore, cannot help but recognise the Western themes in Hills and Texas Chainsaw, at least subconsciously if not overtly. Hooper’s characters are a wary bunch as they venture into remote Texas, all too conscious of the danger posed by the “natives”, while Craven’s Carter family are warned against travelling through the harsh, unknown landscape with its myriad dangers. Both sets of protagonists are defined by their young, smart, attractive and adventurous youngsters (representing the youthful and optimistic pioneers of America), while the Jupiter and Sawyer clans are older, weathered, bereft of culture and, seemingly, humanity (and therefore representing the indigenous savages from a forgotten time).

As the narrative in each movie unfolds, audiences will no doubt feel for the beleaguered white pioneers, be fearful of and repulsed by the savage attackers, and proclaim that good has prevailed when the remaining heroes rally round and the indigenous brutes are successfully wiped out. Audiences may never consciously consider the Sawyer family or Papa Jupiter’s clan as Native Americans, but the thematic link cannot help but be digested at some level and reinforce popular (and erroneous) opinion all the same.

While the movies of Craven and Hooper updated America’s chequered history with cultural bias firmly attached, those of Weir and Eggleston would appear to make a much different statement about their native country…

ADVANCE AUSTRALIA FAIR

"Their crimes were against nature…nature found them guilty”

Australia was a place whose indigenous tribes had not officially been recognised as people with the same favour as the country’s European settlers until the Aborigine Referendum of 1967 – prior to this event, they had been excluded from voting, and held little or no rights to their land and cultural heritage. Indeed, in the early years of white settlers in the country, the indigenous people were routinely slaughtered by European migrants.

By the 1970s, the more liberal among Australian society were starting to become aware of the great injustices visited upon Aboriginals ever since the First Fleet arrived at Botany Bay in 1788.

The first, and most obvious difference between Long Weekend and Picnic at Hanging Rock and their US counterparts is in tone. Both Australian movies are gentler, psychological horrors with a dramatic spine (although Long Weekend in particular carries the same visceral terror as The Hills Have Eyes as it nears its climax). The films pit man versus nature, and casts the environment itself as the antagonist. These two films do carry similar subtexts to The Hills Have Eyes and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre – but with vastly different messages attached.

Set in 1900, the year before Australia declared its independence, Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock presents a narrative without resolution. Like The Hills Have Eyes, Weir’s film features missing children, and with it, the fear of white settlers that their children were vulnerable to attack and abduction by indigenous peoples. In the film, the missing girls and their teacher are never found, and there are several possible, terrifying explanations for why. One is that the million years old rock (believed by Aboriginals, like many geological structures in Australia, to be possessed of an ancient, visceral mysticism) was alive – that it deemed them interlopers and swallowed them whole because they were never meant to be there…which could easily be viewed as a metaphor for European settlers down under.

Indeed, the most common reading of the film is that it represents a dramatic clash between the ancient, unknowable Australia and its white settlers. It portrays the country as foreign and foreboding, a space haunted by the presence of Aboriginals even in their absence, and the Europeans who sought to dominate it as the alien presence which must (and shall) be overcome. The titular Rock, like similar places of geological interest in the country, are not just revered by indigenous peoples for their apparent mysticism – they represent articles of cultural value, too, as it is these rocks, caves and outcroppings that are home to the visual representations of Aboriginal ‘storytime’ – the people’s methods of recording the history of Australia. When white settlers interfere with such artefacts, they represent a threat to both the environment and to what may be the most ancient recorded cultures on earth.

It is here that the subtextual narrative of Picnic at Hanging Rock differs from The Hills Have Eyes and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre – in Weir’s film it is the ancient, uncouth, unrefined presence that is victorious. There is no great white hero to rally round and rescue the missing girls and their teacher.

There are other (chiefly sexual and feminist in nature, dealing with the girls’ apparent homosexuality) subtexts divined by critics and audiences, all of which have significance and make for enlightening readings of the film - but the possibility that the girls, who drift into a hazy, dreamlike state as they traverse the rock, then vanish without trace or explanation, were swallowed up by the hostile terrain itself remains the most frightening prospect presented by the narrative.

In Eggleston’s very psychological film Long Weekend it is nature itself that fights back against the human interlopers – a married couple who treat the environment and creatures around them with disregard and contempt. In Long Weekend, the white, middle class Australian couple are both the pioneers AND the savages – as they venture into the wild unknown territory, they start fires, spray insecticides and kill dugongs and kangaroos, doing everything they can to pollute and desecrate the environment as readily as they attack each other’s behaviour in their doomed marriage. Eventually, the outdoors fights back, and they are beset by birds, dogs, snakes and every element of the environment they cared so little for.

This can in itself be read a number of ways. The most overt reading is as a call to action on climate change. When European settlers started to make Australia their own, they did bulldoze nature to create bustling metropolis, and the country’s coal-mining industry continues to massively damage the environment, excavating large swathes of rainforest in order to transport coal to the coast, to vast seafaring vehicles that in turn are destroying the Great Barrier Reef, one of the natural wonders of the world.

In addition to the above, the taking over (and desecration) of the Australian landscape was accompanied by vile treatment of the aboriginal peoples, who feel a deep connection to nature and the land that the European Australians cannot share. There is a widely held misconception that the Aboriginals were not even considered people prior to the 1967 referendum – that their rights and responsibilities were covered by the country’s Florae and Faunae Act – that seems relevant when considering it is the Australian environment itself (an environment the Aboriginals are thought by many to be an intrinsic part of) that inflicts its horrors upon the film’s protagonists.

Overall, in terms of social and cultural attitudes, there exists a stark contrast between Craven and Hooper’s US films and those of Weir and Eggleston. The former’s offerings would, inadvertently serve only to maintain the status quo, furthering a dangerous narrative that has contributed to the ongoing desecration and destruction of some of mankind’s oldest peoples. The Australian filmmakers appeared at least to show a level of cultural awareness and a respect for history that, on one level, could be argued sought to recognize and apologize for the crimes perpetrated by pioneers against an indigenous population and an alien landscape.

McNeely (2018) considers that the horror movie is tied to the cultures that their audiences are immersed in. When we watch (and when auteurs create) horror movies, they cause us to reflect on the trauma within us, which is why we relate and react to them so well. Horror films provoke a more visceral reaction than any other genre, and not purely because of the blood and murder, shocks and scares. It is in the rural, inhospitable Badlands of America and the supposedly savage natives that the true horrors of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes lie; it is in the hostile climate and landscape of Australia, filled with terrible creatures and strange indigenous tribes, that Long Weekend and Picnic at Hanging Rock find what is most haunting to audiences and challenges not only our own trauma, but our own prejudices.

In all four films, the protagonists are shown as people venturing into territory they do not fully understand, and are not capable of forming a symbiotic relationship with – for which they are punished. At the very least, Weir and Eggleston’s films gave an acknowledgement of that which came before – though it might never be fully understood – was to be considered and respected. In the US, the great western horror movies of the 1970s showed a savage beast that must be tamed; in Australia, they showed us one which can never be.

One parallel, however, was certain. These four films shocked America, Australia, and the world. They were at once lauded and lambasted, championed and censured (and in some cases banned). In terms of horror cinema, each contributed to a permanent change of the genre landscape, and became fundamental entries into a ‘New Wave’ of genre cinema in each country that would not be soon forgotten.

If horror cinema is indeed meant to challenge, then it is in our reaction to that challenge that we learn more about ourselves. Do we cheer for Leatherface as he swings his chainsaw, or do we grit our teeth, clutch our armrests and hope for the interlopers’ survival? Do we consider the missing children of Hanging Rock to be victims of the white settlers’ own transgressions, or do we seek to blame the surroundings that did not invite them in the first place?

In considering our reactions to the images on screen, we turn the mirror on ourselves, and examine our own attitudes to the political, social and cultural environs they were made in.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Buckmaster, Luke (2014) Long Weekend rewatched – mother nature toys with her callous human prey

Cook, Rob L (2013) The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Decay of The American West

Crewe, Dave (2015) Picnic at Hanging Rock: Australia's own Valentine's Day mystery

http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2015/06/03/picnic-hanging-rock-cheat-sheet

Ebert, Roger (1998) Picnic At Hanging Rock

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-picnic-at-hanging-rock-1975

Johinke, Rebecca (2010) Uncanny Carnage in Peter Weir’s The Cars That Ate Paris

http://openjournals.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/SSE/article/view/4745/5489

Keesey, Douglas (1998) Weir(d) Australia: Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1edc/0745df9010b7cd1e61b77b8b1ef9b0382659.pdf

McKendry, David Ian (2015) THE HILLS HAVE EYES Is Based on a REAL Story!: The Sawney Bean Cave Clan http://www.blumhouse.com/2015/11/20/the-hills-have-eyes-is-based-on-a-real-story-the-sawney-bean-cave-clan/

McNeely, K (2018) How Cultural History and Trauma Shape Our Fears in Film [online] Available at: https://www.salemhorror.com/news/2018/8/20/how-cultural-history-and-trauma-shape-our-fears-in-film [Accessed 25 August 2018]

Muir, John Kenneth (2009) Cult Movie Review: Long Weekend (1979)

http://reflectionsonfilmandtelevision.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=long+weekend

Nazza (2011) Picnic at Hanging Rock: A Review

http://feministing.com/2011/09/27/picnic-at-hanging-rock-a-review/

Newman, Kim (2015) Empire Essay: The Hills Have Eyes Review

http://www.empireonline.com/movies/empire-essay-hills-eyes/review/

Picture This (no date) Homogenization, Protests & Outright Rebellion: 1950s: Native Americans Move to the City—The Urban Relocation Program [online]. Available at: http://picturethis.museumca.org/timeline/homogenization-protests-outright-rebellion-1950s/native-americans-move-city-urban-relocat-0 [Accessed 25 August 2018]

Risnes, Matt (2013) Foraging For Subtext: ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ 1974

http://www.comingsoon.net/movies/news/576425-foraging-for-subtext-the-texas-chain-saw-massacre-1974

Zinoman, Jason (2011) Shock Value. London: Penguin Books Ltd

Mark loves horror, it's history, Art House films and he also loves to make art.

Be Sure to Check out his work

This week on Beyond The Void Horror Podcast they sit down with Director Anthony Diblasi about his upcoming horror movie "Extremity". Plus review "Dread" & "The Midnight Meat Train". It's a big episode you won't want to miss. You can listen here or you can Listen/Subscribe on iTunes here!